From the soundtrack of a Sean Connery film (the screen version of Umberto Eco's medieval mystery 'The Name of The Rose', not a James Bond movie), to the so-called 'ambient' or 'chill' room at the Glastonbury rock festival in 1993, the presence of Gregorian chant in our lives - over a thousand years after its existence was first recorded - proved that there's life in the devotional sound beyond the realms of grey-haired calligraphers swaying their quills in time. Old age music for the New Age, or timeless musical liturgies to the glorification of God? Well, both really...

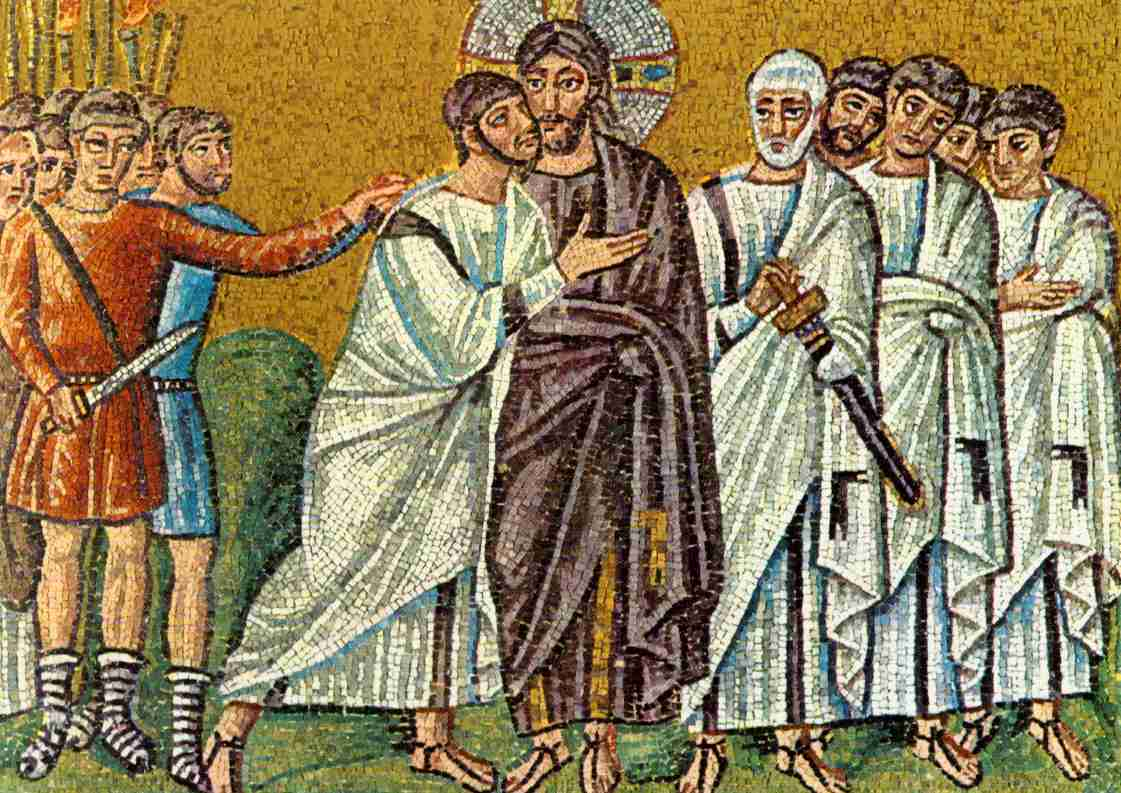

This fundamental Catholic liturgical song is habitually associated with the first Pope Gregory - Gregory The Great, now Saint Gregory - who occupied the position of pontiff from 590-604 A.D. (He is also, credited with the dispatching of a mission, led by St Augustine, to the British Isles to convert the area to Christianity.) Yet there is little evidence to show he actively contributed to its foundation -apart, obviously, from donating his name. It's said he was enthusiastic and sympathetic, but the impetus came from the monasteries of the church of Rome across Europe, parallelling the scribes' and theologians' tussle with the first Catholic liturgies.

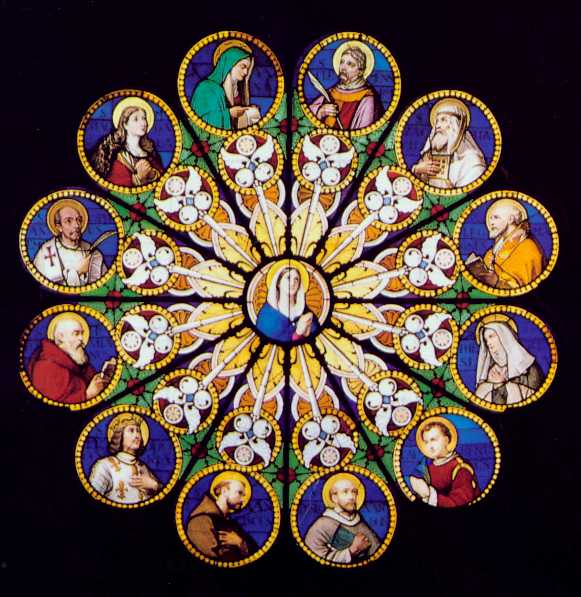

The written record of Gregorian chant dates from the 9th century, though it's fair to suggest this doesn't accurately reflect the music's antiquity. A hundred years later, French Catholic revivalist monks breathed new life into the form, and since then German and Italian baroque music forms and Gothic choral styles of the 16th and 17th centuries have augmented the chant tradition and revived its popularity to such an extent that it has remained the fundamental Catholic treatment of the psalms, and its basic musical expression. (Listeners may be interested to note the delightful handling of Bach's choral work by the monks of Notre Dame Abbey in Ganagobie. Many of Europe's great composers and poets have contributed to the chant's evolution.)

What isn't in dispute is the chant's timelessness. It appeals to and moves the listener through its simple devotional quality, directness, and bold, repeated melodies. It is plainsong; that is, irregular in its rhythm, and either sung solo, in unison or quite frequently 'call and response', but always monophonic. The text is always the psalms of the Bible. There are eight Gregorian tones, melodies prescribed for the psalms, and a particular psalm has a suitable 'inflexion on the ending of the verse (the 'call' part) according to how it should connect with the 'response' verse (sung in unison).

The chant's main billing is frequently supported by an unadorned, evocative, seemingly meandering organ playing with an echoey and reedy quality. The impressive piped sound acts as punctuation, or a reflective repetition of the vocal theme, and varies the music without diminishing its hypnotic sparseness.

Naturally, though the words are sung in Latin or French or whatever tongue, the effect is more acute on those listeners whose religious beliefs are reflected in the oratory and for whom the treatment is a recognisable facet of their creed. But for non-Catholics - agnostics, even - there is something intangibly appealing about the monks' song, and its expression of a solitary, dedicated life and its assured purity of voice and melody.

The senses of seclusion, agelessness and devotion are heightened by the atmosphere of the recording here, all captured in the austere and resonant abbeys, chapels, monasteries and cathedrals of the choristers. Some of the original chants were first written in the 9th and 10th centuries. Most sequences are from Benedictine orders from France, whose monks' innovations through the centuries within the tradition of Gregorian chant (or, in the case of the Prieure de Ganagobie, Dominican) have put them at thet forefront as interpreters of the music form. But the Benedictine Monastery of Einsiedeln, a baroque abbey dating back to 934 A.D. nestling near the Swiss and Austrian borders, produces a clarion voice noted for its own distinctive character.

The Benedictine monks featured are those who have answered the call from God to dedicate themselves to a life according to religious dictats (which thankfully permitted the production of the liqueur now known as Benedictine). Some have felt the chill draught of unwelcome publicity intrude into their austere and solitary lives: the monks of St Marie-Madeleine de Marseille, who founded their order in 1866, moved to Hautecombe in 1922 and decided to uproot again and install themselves in the rustic surroundings of Durance valley in Provence in 1987 - more suitably to the pursuance of a hermetic existence away from the prying eyes of tourists (this was before the days when Peter Mayle's best-sellers brought floods of British visitors to the area). But beyond the business of the devout simply singing God's or the Virgin Mary's praise, the evocative sound or Gregorian chant has a umcjue appeal. It has a soothing, contemplative and deeply spiritual effect on the listener (both secular and sacred) that is unmatched in Western music.

Only the Sufi mystics of Islam and their mesmerising Qawwali music approach the atmosphere of devotional and spiritual depth. But whereas the magnetism of the Sufis' expression lies in its improvisation and almost sexual build-up to an ecstatic musical climax, with Gregorian chant it's the profound restraint of the singing, the humility and even vulnerability of these singers who've denied themselves in order to serve another, that is ultimately so wonderful.

Damien French